冒険のためのマニュアル

Manuals

Japan has manuals for everything. There are manuals for how to fill out all kinds of paperwork, manuals on etiquette, manuals on how to properly enjoy certain dishes, etc. But there are loads of manuals for the mundane things as well.

In my kitchen alone, there is a sticker on my countertop with countertop usage instructions. To the right is my sink basin which has a waterproof sticker with sink basin (not the faucet) usage instructions. To the left is my range which has one caution sticker about this and that and another warning sticker about other things, all related to proper and improper usage. Above my range, my kitchen hood has a sticker with advisories. These are all applied by the manufacturers. Additionally, my landlord used a label printer to print even more usage information and attach it to features around my apartment, one even on my already-labeled kitchen hood.

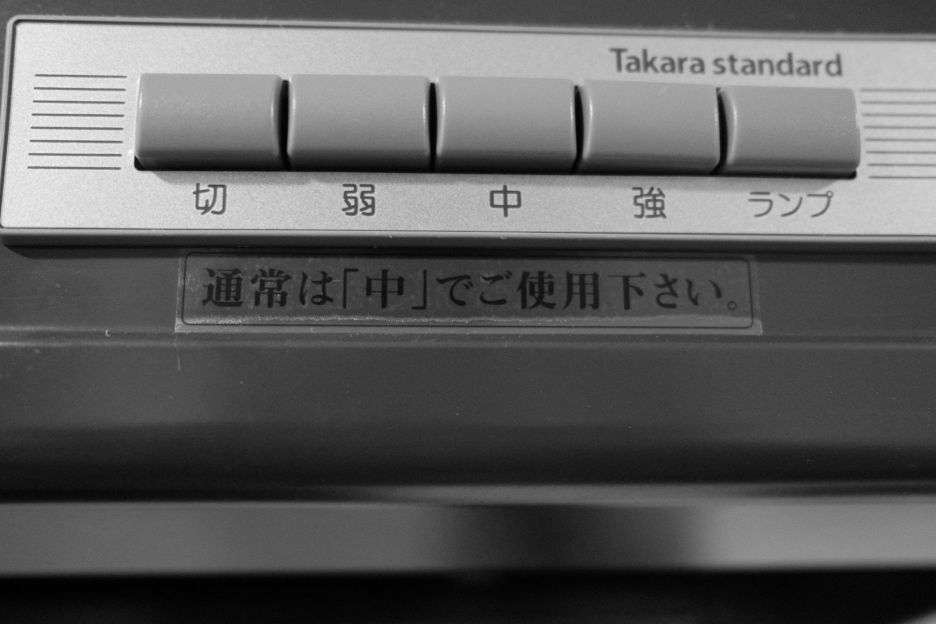

"For ordinary usage, please use medium [中]." Roger that.

On my wall next to my kitchen hangs my air conditioner remote control. There is a landlord-attached sticker which reads, "エアコンに向けて操作してください," or, "point at air conditioner and operate." On the overhead vent in my bathroom is a label which reads, "月に一度掃除してください," "please clean once a month." On the side of my mirrored door of my bathroom's medicine cabinet is a sticker which reads, "上部にダウンライトがある場合その下で扉を長時間 止めないでください," or "if there is a downlight above, please do not stop the door under it for a long time." I'm not even sure what that means or why it's important--the further I open the cabinet, the further away the door gets from the light, and proximity to the light is the only thing I can think would be an issue, but even then I'm not sure why as the light is an LED one. On the left side of my shower door is a manufacturer-attached sticker on how to remove the door from its hinge, and on the right side is another sticker showing how to operate the lock--twist right to lock, left to unlock.

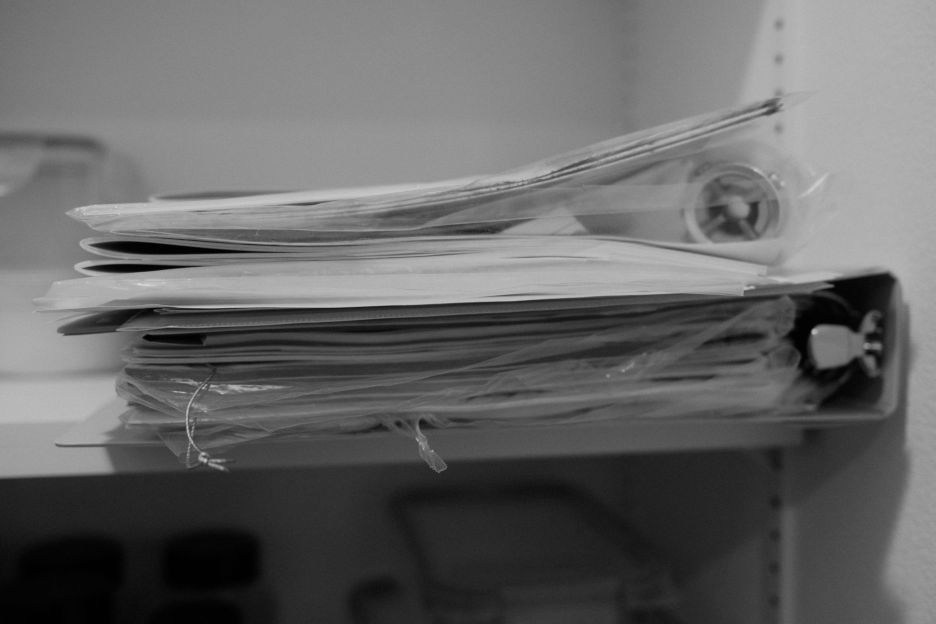

My apartment came with a binder of manuals. These ones are paper manuals, the manuals for operating my shower, faucets, toilet, range, air conditioner units, and other room facilities. This manual is unique to my room. Other rooms are not guaranteed to have the same model or manufacturer for similar facilities and devices. The binder holding the manuals for my apartment--mind you apartments such as mine come unfurnished in Japan--is 2 inches (5 cm) thick.

The things on top of the binder are the manuals for my washing machine, refrigerator, range/oven combination, desk, etc. I had one for my previous mattress as well, but I retired the manual when I bought a different mattress.

The real estate agent who handed the apartment over to me introduced me to the apartment's manuals. I must safeguard these. They are to be handed over to the next tenant who will become custodian to the tome.

I admit I have never read any of these paper manuals. I did thumb through the contents of the binder, though, because although I held it in my own hands, I could not believe there was a 2-inch binder's-worth of things considered important to know about an empty apartment.

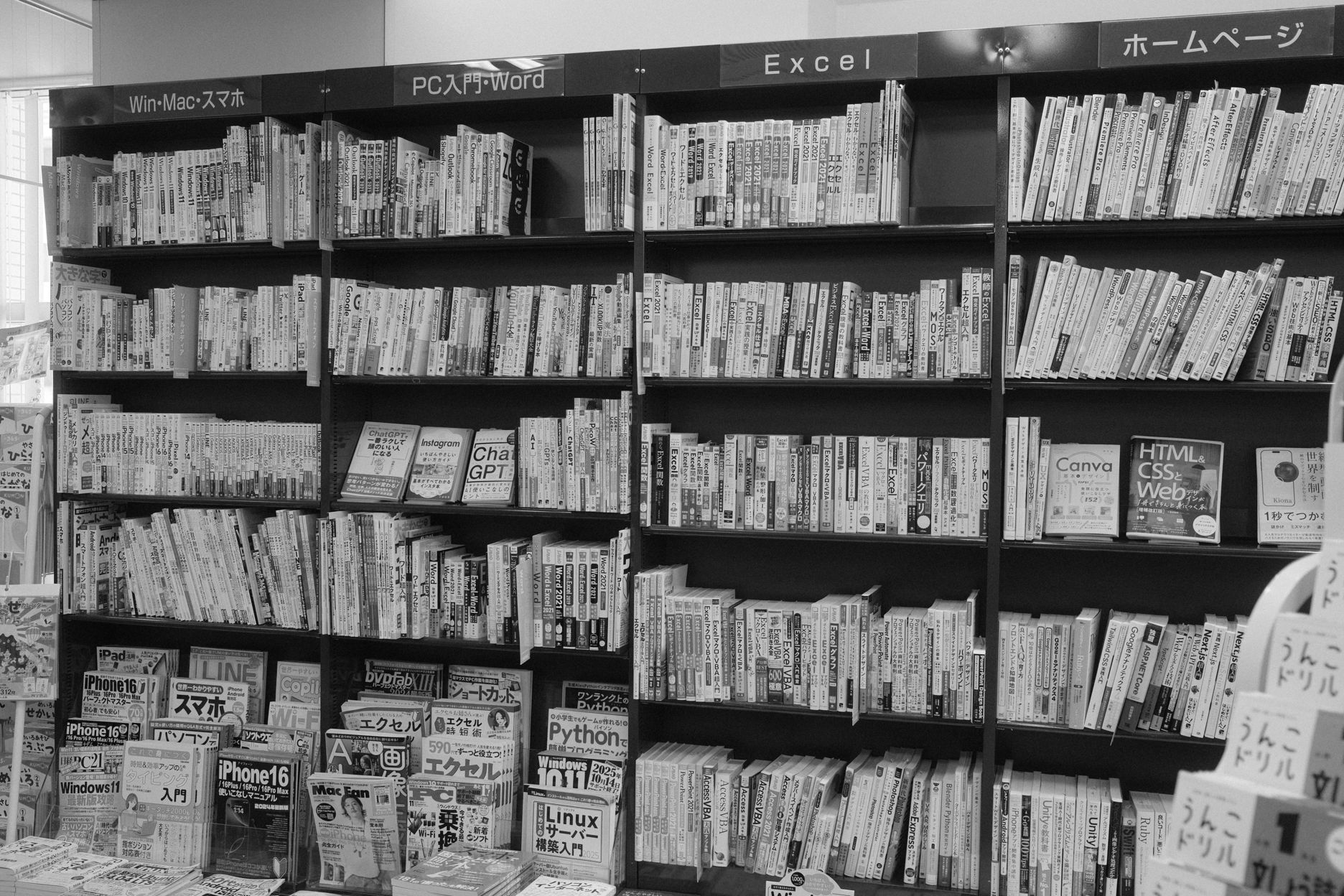

Go to a Japanese bookstore, and you will see many manuals. I was at first surprised to have not seen a section called "Manuals," but then I realized there are so many of them that they are topically sorted. Here is a photo of manuals related to digital things. In this context, the manuals are more like how-to books, but online we'd find the same content labeled as FAQs, tutorials, or training material.

If you zoom into the photo and can read Japanese-English, you will see manuals for not just Microsoft Word and Excel but also for Instagram, configuring Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, using YouTube and Google, using Line (the most popular messaging app in Japan), using Zoom, using your Pixel phone, and using a Chromebook, among many other things.

Why?

This is an interesting question. In short, I don't know. The print media business for things other than register-side tabloids is still alive and well in Japan, but that doesn't explain the nature of some material, such as all the manuals. I want to answer this question convincingly. That will take time and some social studies I have not performed yet.

Manuals for Adventure

I think a lot about exploring all over Japan. I'd like to visit all the nooks and crannies. Travel is fun, but my motivation is that I want to see sides of Japan I feel somehow drawn to without having yet experienced. If this sounds weird, there will likely be a future post about an affinity with Japanese things that I had starting from a young age despite never having experienced such Japanese things firsthand. Put another way, more concretely, I suspect traveling all over Japan has things to teach me.

Nowadays very many people stay mostly in one place all of their life. They may travel here and there, but they return to their familiar city. While traveling, it's easy to keep to yourself if you so choose. Go there, take the pictures, eat the food, retire to your personal hotel room, fly out. Hundreds of years ago in Japan, people did the same thing--less the pictures--but they weren't flying. Most of them were walking (within the confines of the island, of course). Even further back, longer journeys were mostly not for fun or for satisfying curiosity but were for official business or trade.

A road called the 東海道 (toukaidou) (literally "eastern sea road") connected the large political and population center of Kyoto to Tokyo. Nowadays, the Toukaidou Shinkansen runs generally along the route of the old road. So people still travel the Toukaidou, but they practically fly along the ground, keeping to themselves in their seats on the bullet train, covering the distance in something to the tune of two hours. But back then, I wondered, what kind of experiences might you have on the toukaidou? It takes between 15 and 20 days to walk assuming you only walk during the daytime. There are 53 "relay points" (宿場, shukuba) along the way. These relay points were rest spots and inns. What kinds of people would you meet? How much better did そうめん (soumen)--simple thin, white, wheat noodles--often served cold in a dish of soy sauce and vinegar, taste after walking for so many hours? How much better did a hot spring feel after you had to work for it? How much nicer was a roof over your head when rain came down in the middle of your journey?

The toukaidou of old is no more. The original paths are gone in many places. They remain in some, such as near 箱根 (Hakone). The relay points remain to some degree as well, sometimes largely together, kept up mostly as tourist attractions, other times just an engraved rock or sign marking the location of the old shukuba.

I had heard about the toukaidou some time ago, and in my search for curious, niche writings on Japan, I had come across Patrick Carey's Rediscovering Old Tokaido: In the Footsteps of Hiroshige. At over 1万 (10,000) yen (back when the yen was 100 to the US dollar, that's $100) in hardback, I didn't buy it. But I did read everything I could find about it. It was a recreation of the toukaidou route with photographs of sights and relay stations along the way. An 浮世絵 (ukiyo-e, woodblock printing) artist named Hiroshige, who lived from the late 1700's to the mid 1800s, walked the toukaidou and created woodblock prints of various sites. Carey succeeded in finding the locations and subjects of many of Hiroshige's prints. Carey's work was published over 20 years ago, and I wondered if there weren't more modern chronicles of the journey.

There is a Japanese YouTuber with a channel named やんまんショウ (Yanman Show?) which chronicles a journey across the toukaidou, playlist here at the time of this writing, now 5 years old. From this I learned two things. The first is that it is still realistic to walk the toukaidou, and the second was that I wanted to do it myself.

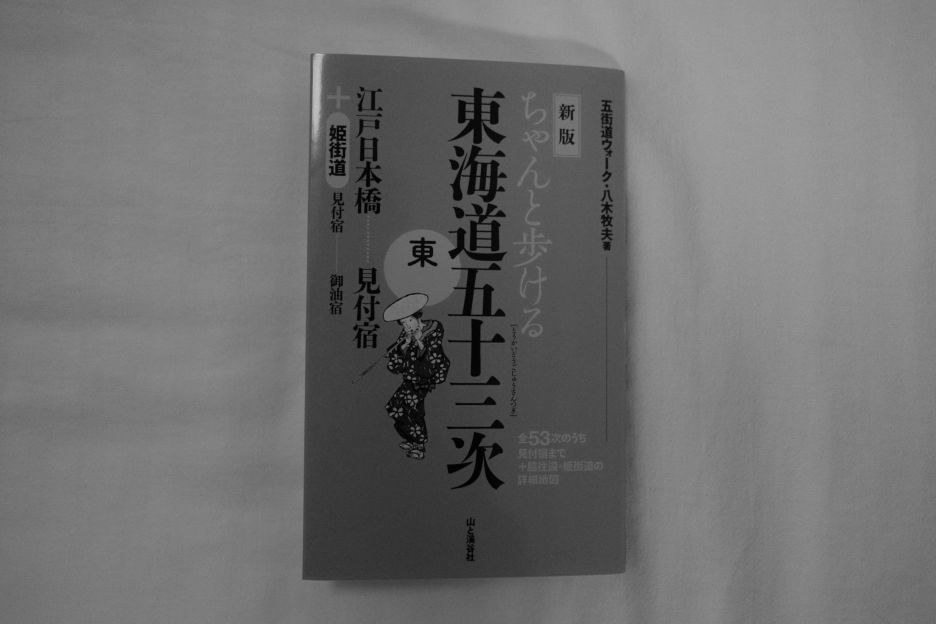

I didn't want to recreate the route from tens of minutes of videos, expensive books, or by collating blog posts from people here and there across the years. Surely there is a modern, complete description of the route. I retreated from the general internet to Amazon where I searched for books--there had to be manuals on this as well. And sure enough, there are. Most were published twenty or more years ago. I found one which is exactly what I was hoping for.

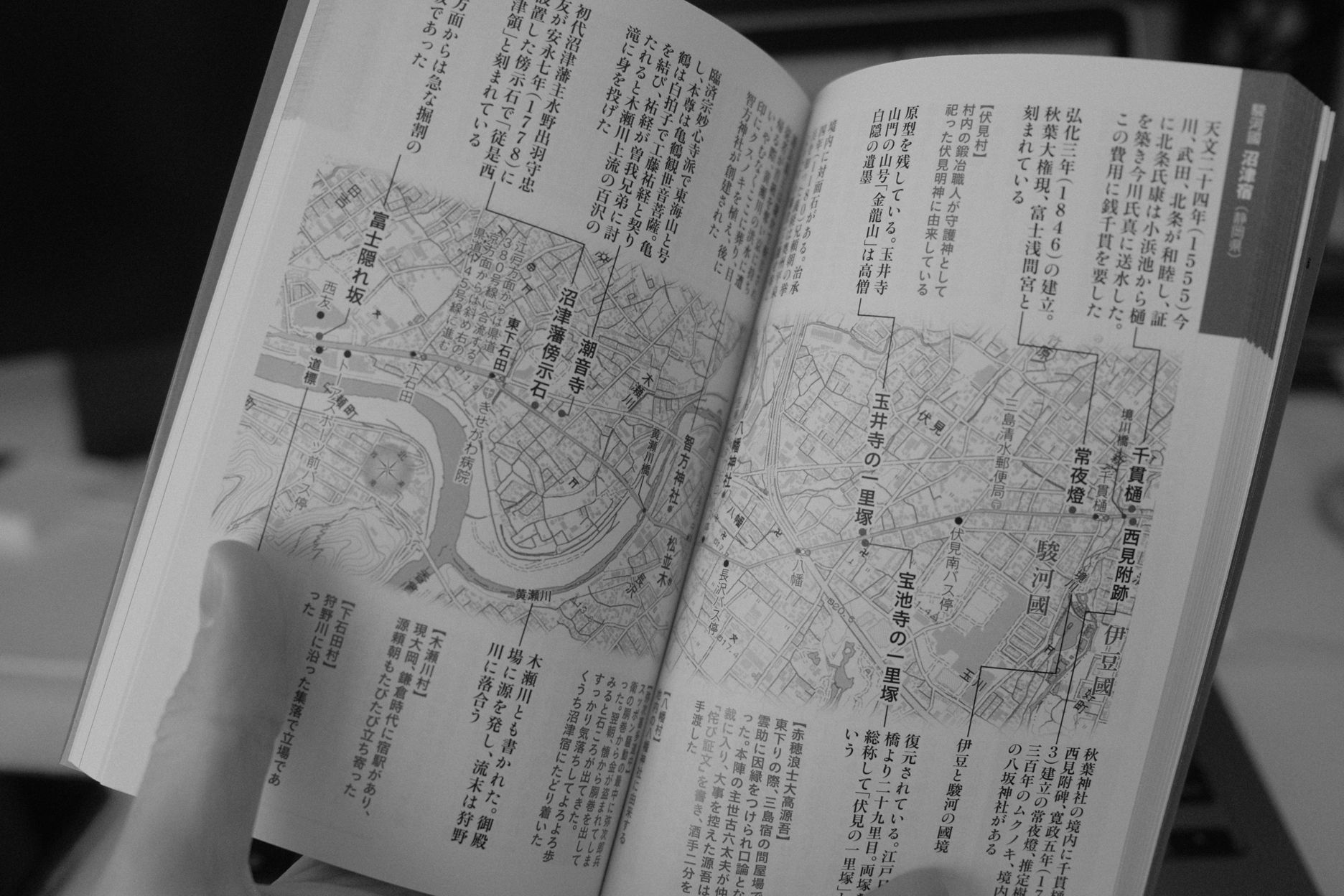

東海道五十三次, The 53 Waystations of the Toukaidou, reads the largest text running down the center. To the right is ちゃんと歩ける, which I roughly translate as, "walk it authentically." This book was published in 2019 and is focused exclusively on walking the Toukaidou. This book details the eastern portion of the route, a second book the western portion. It is essentially an annotated map.

Being an annotated map, it is practically out of date the moment the map is drawn, as there is always construction happening somewhere along the main throughfares in Japan. But by no means is "out of date" in this context what it is for similar books published in the 1980s. This book outlines the general route I will follow, and the fact that it annotates sites of interest and, most importantly, the waystations, is all it needs to remain useful over a long period of time. Comically, the book calls out select convenience stores and hotels along the way, the latter with their phone numbers listed. That is generous, but is such minute detail necessary? I will just smile with gratitude.

After, or perhaps leading up to the time when, I walk the toukaidou, I have an idea to create a more accessible map. That's a topic for another potential post, though.

Two Journeys

This marks the beginning of two journeys. The first is of course walking the toukaidou. The second is everything leading up to it. I don't know when I will start the walk, but as it takes two to three weeks, I will need to do some planning. Not just arranging vacation at work, if I am still employed by someone else at the time (yet another potential post), but also arranging my gear, selecting roughly how far to walk each day, booking hotels in advance, etc. This will take some time, and in that span, who knows what will happen.

As for the walk itself, my only goal is to be open to everything it has to teach me, both about Japan and about myself. The journey starts at 日本橋 (Nihonbashi) in Tokyo, and the journey ends at 三条大橋 (Sanjyou Oohashi) in Kyoto. Coincidentally I was just in Kyoto last weekend, and while there I took this photo facing down Sanjyou Oohashi, the same direction a traveler would face finishing the toukaidou, facing into Kyoto.